|

RUSSELL P. REACH

October 19, 1958 - November 11, 2007 |

Personal Testimony

~ listen ~

(click here)

~ download ~

(right-click and "save link/target as")

Memorial Service

~ listen ~

(click here)

~ download ~

(right-click and "save link/target as")

-

Remembrance by brother Ronald Reach

For those of you who don't know me, I'm Ronald Reach, youngest of the Reach brothers.

We're here today to celebrate the life of a person - who was a friend, a devoted husband and father, a good son - he was our brother, Russell Reach.

It's a certainly challenge standing here before you, cause not only am I very sad over the passing of my brother, but as I stand here, it seems quite a daunting task to give a eulogy, for a person who is the best eulogy-giver ..... I have ever heard.

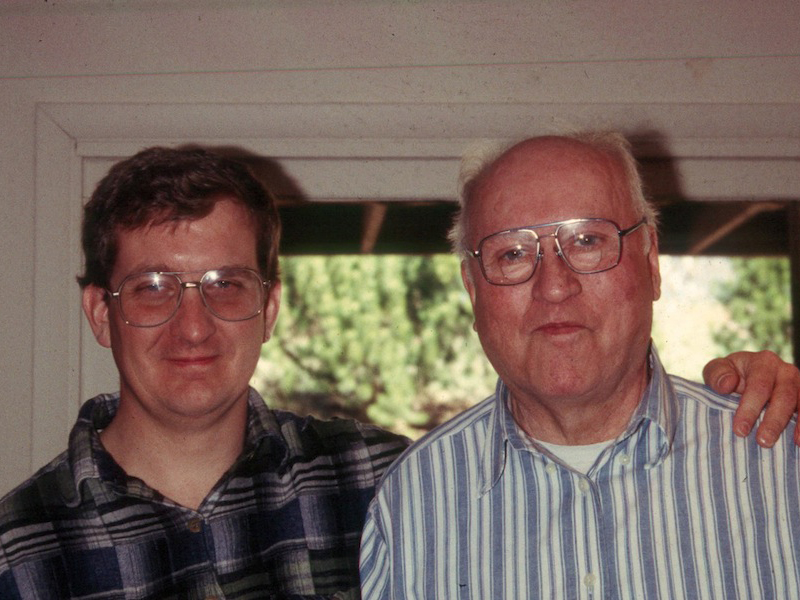

When our dad, Roy Reach, passed away in 1997 in Jacksonville, Florida, there were several speakers at the funeral that day, as many of you who were there may remember:

But Russell's eulogy to our father stands out in my mind as the most moving, not just because he was my brother and thus, I could relate to his feelings about the passing of our father; but rather, I was so profoundly moved because Russell had many talents, and amongst them, the gifts of writing and of public speaking, and he could effect the audience in such a way as to move them to memory, to conjure the essence of that person, to put on a pedestal the best and most admirable aspects of that person's personality.

He had vision beyond sight: an ability to see deeply into a person's character, into what motivated them, into what made a person likeable, a vision into what it was about that person that elevated them to the status of greatness.

He spoke in such a magical way about that person, so brilliantly eloquent, that for a still moment you would be swept away, tricked into believing that the person was standing yet before you, and that perhaps they were not gone from us, after all. His words would, for a brief second, almost bring that person back again.

Then again in 2003, when our sister-in-law Lauren passed away - Russell delivered such a moving eulogy at her funeral, and once again, with no exceptions, his words were again so descriptive and well written, as to capture the essence of who Lauren was with his words and imagery.

There are, no doubt, many other eulogies that Russell has given, at many other funerals. There are likely many here today who have heard him speak on these occasions, so you may agree with me when I say: he took great pride in honoring these individuals with his words.

After these two funerals, at the reception, Russell was very proud of the outstanding job he had done in writing and delivering these eulogies. He wanted them to be the best. Even in the midst of his sorrow, he would be beaming with pride over his accomplishment. He would pull me aside and say "So what did you think of it? Was my eulogy the best one!? Do you think I did them justice? Do you think my speech captured their essence?"

And I would smile and patiently answer, "Yes Russell, it really was fantastic. It really was the best." And I really, really meant it.

So here I am before you all now, called to stand here and do my best, writing a eulogy for the expert eulogy-giver. And Russell, I will now try to take your lead, and do my very best. You are a good brother, and I pray I have learned by your example. I will try to do you justice. So for what it's worth, here it is.

As anyone who has known Russell for any length of time, you know that attention to quality and detail did not stop at his eulogy writing. Indeed, in whatever Russell did, it was never halfway. Whether it was in his career, being a father, remodeling his house or singing a song, whatever the endeavor, Russell would dive in head-first, never leaving any stone unturned. Russell was a person who did nothing without imbuing it with quality; Russell was a quality person.

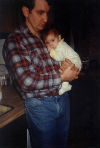

I have known Russell since the day I was born, when he held me the day they brought me home from the hospital. I could speculate that perhaps it was on that day that day that Russell decided he loved babies and children, and that one day he might like to become a dad himself, and as we know, he did just that, fathering six of his own children.

My first memory of Russell is from Sudbury, Massachusetts, from 1970, back when I was only four years old, and Russell would have been twelve. Russell told me he was going to take me for a ride on the back of his Schwinn bicycle - I thought we might be going for a ride just down the street where we lived on Pekham Circle ...... but of course, Russell had far more grandiose plans!!! He had packed us both a lunch, and we boldly headed off down the main road towards town, me riding on the back of his bike holding on tight to my big brother. Of course, I very much doubt that Mom knew about all this! - She never would have approved of such a foolhardy venture.

So there I was, wind rushing by, cars passing left and right, me holding on for dear life - what a thrill it was!!!

Whenever Russell got a grandiose plan in his head, there was no stopping him, and off he would fly in pursuit of whatever that something was, with that clever, self-pleased look of absolute glee, half-smirking, and that mischievous sparkle in his blue eyes.

At night in Sudbury, as a small child, if ever I couldn't sleep or was frightened over some nightmare, Russell would come and comfort me - bring me some water, scratch my back, sing me a lullaby .... 'til I was off, back to sleep again. I could always count on his kindness.

And speaking of Sudbury Massachusetts, where I and my 5 brothers were first raised, let me just tell you ....... this town of Sudbury is a town with which Russell was particularly enamored. At that time, Sudbury was a small town. A suburb of Boston, it is a place rich in history of Colonial America, on the road between Lexington and Concord, a town that was on the path of Paul Revere's famous ride. It's a place that in autumn the trees sparkle with a bright orange and yellow glow, somehow more brilliant than in any other place you have seen; in winter, white blankets of snow and Christmas lights, and in the spring and summer, fragrant flora and balmy breezes.

Not only rich in beauty, Sudbury is a place that embodies the American Spirit. Sudbury is the town Russell called home, a place that inspired him - and that he spoke of with fondness, and with frequency his entire life.

This is where Russell Reach was from. Russell wants you to know this.

I think that coming from this place, had somehow given Russell a most sentimental nature, a spirit that longed for beauty and goodness, and it somehow imbued Russell with a vision, an idealism that included a sense of integrity, honesty, ingenuity, and invention. Coming from Sudbury contributed in giving Russell an ideal of freedom, tenacity and determination.

So crucial to his formation as a person, if Russell had been raised any other place than Sudbury, he would never have become the Russell we have known for so many years. So important was this place to him, he took many trips back to his hometown over the years, going so far as to take his children there, to the Fourth of July parade, as he had done so many times as a boy.

Why did he take such measures to expose his children to this place, to these experiences? He did it because it was important. It was important that they see the place that had inspired and influenced his whole character to such a degree, so that they, too, might catch the spark of this special and inspirational town. It was a gift he gave to his children.

After we moved from Sudbury down to Florida in 1972, I can remember another incident that happened that is exemplary of Russell's character: I was 6 years old at the time, and our family was visiting our Grannie Reach in Daytona, Florida. We had all gone to the beach, and I had opened a large metal door at the hotel onto my foot, which caused a deep injury to my big toe. The hotel had no first aid available, so with out any hesitation, Russell scooped me, an 80-pound child, up in his arms, and RAN with me nearly 1/2 a mile in his arms back to the car, my foot bleeding the whole time. He got some fresh water and poured it over my injury, cleaning it himself.

It was a heroic thing, a selfless act, an act of such kindness that this single incident has effected who I am as an adult.

Now, this is not the behavior one would generally expect from a typical 14 year old boy; but Russell was NOT a typical 14 year old boy.

When we later moved to Toledo, Ohio, Russell became very popular young man at Anthony Wayne high school. Not only was he in the marching band, but he acted in school plays as well. Russell was an outstanding character actor, who could do many impressions and voices, and when Russell acted in the high school plays, he would steal the show. He had a flair for music and singing. Our mother took me to see all Russell's plays, and watching him on stage inspired me to want to be in plays as well, which in fact, I did all through high school and college, and beyond.

In the marching band, Russell played the bass drum. As he did with everything he pursued, Russell took tremendous pride in his school band, boasting many times that "The Anthony Wayne Marching Generals are the BEST marching band in the country!!! In his excitement and enthusiasm, walk around the house, mimicking the announcer at the football games, saying "Anthony Wayne High School Presents - Under the direction of Mr. Robert Shoemaker, THE ANTHONY WAYNE MARCHING GENERALS!!!!" And indeed, they really were the best, winning many awards for their original outstanding presentations, and playing at events across the United States. We would all go to the football games, not to see the game, but so we could see Russell perform with the Marching Generals.

At half-time, I would stand by the fence to watch the musicians file out onto the football field, taking special care to look for my big brother, who was the easiest in the bunch to pick out, his giant bass drum strapped to his front, arms flailing wildly, marching in triple time as the band played with sheer abandon. Their uniforms were not the typical marching band attire, but were modeled after the Revolutionary war Uniforms, with the black three-cornered hats, royal blue tailored waistcoats, spats, and white gloves. What appropriate attire for a person who came from a place like Sudbury. Russell was nothing short of magnificent!!!

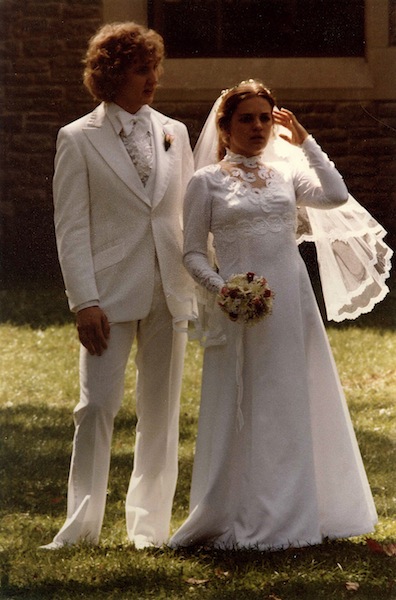

Yes, Russell was a Renaissance man at Anthony Wayne, earning high Academic awards and going on to enroll at Miami University of Oxford, Ohio. The first Thanksgiving of his freshman year at college, Russell came home for the holiday, bringing with him not only a new collegiate look and attitude, but also a big surprise ....... a very pretty girl named Beth Brennan. During that trip, I personally introduced Beth to the joys of what it must be like having a 9 year old brother that INSISTED that you watch them do magic tricks ...... LOTS AND LOTS of magic tricks. Beth was, however, very patient with me, thanks for that, Beth.

It seemed that indeed, Russell had found a rarity, the needle in the haystack ...... she was young woman who matched Russell in every way with regards to kindness, intelligence, patience, integrity, enthusiasm, wit, and humor. To me, she was the kind of person one might want to have for a sister-in-law.

Soon, Russell announced to our family that he and Beth were to be married. But this was not the only news that came - they also announced to our family that they both had decided to accept Jesus Christ as their Savior, and along with that decision, they would both be moving to Greenville, South Carolina, so that Russell could continue his studies at Bob Jones University. This was a time of great change in Russell's life, having a new wife, a new school, and a newfound spiritual path. Russell started taking classes at Bob Jones, and got a job at a local machine shop. Russell worked very, very hard, both at his studies and at his job.

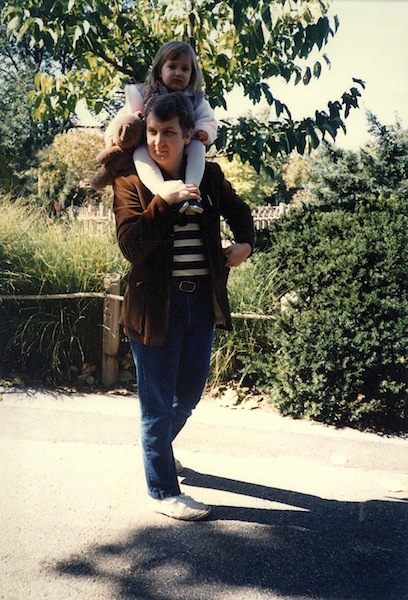

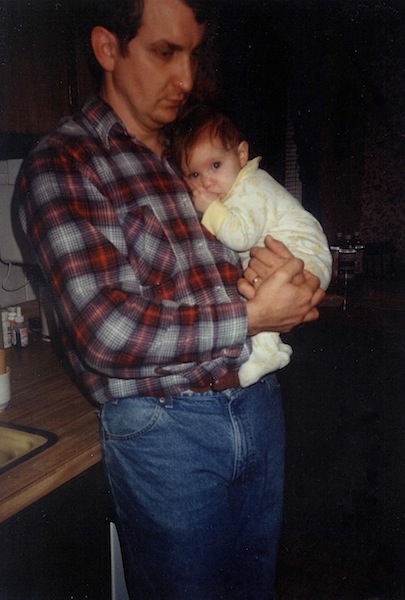

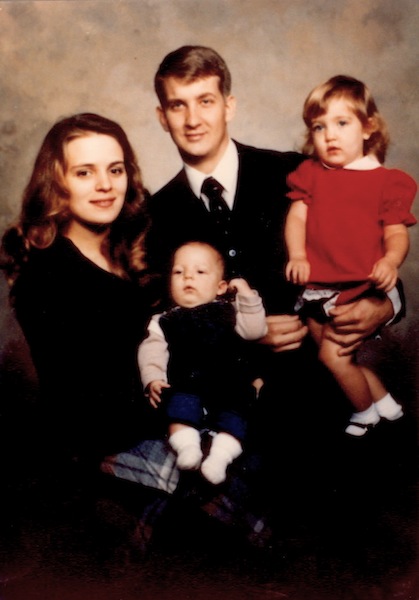

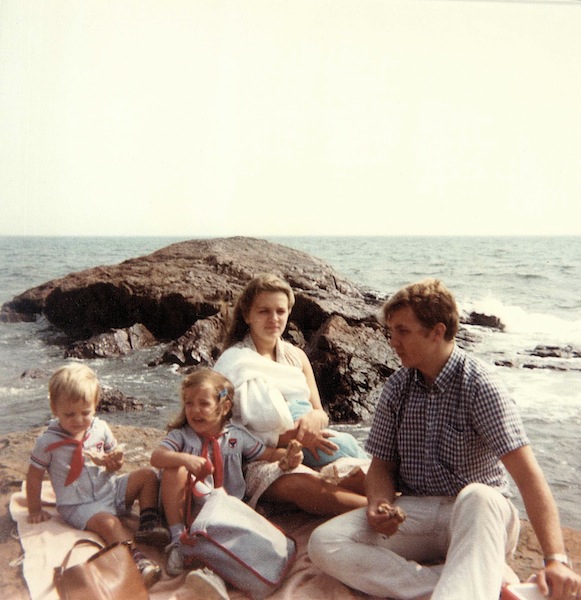

Not long after Russell had started his academic career at Bob Jones University, Russell called and announced that he and Beth were to have their first baby! Baby Emily was born in September 1979, and over the years, was followed by five more children: Philip, Daniel, Rebecca, Sara, and Abigail. Each of these six children, in turn, were every bit as precocious and unique as their parents.

In Greenville, with Beth working also, as well as caring for their young children, Russell eventually graduated from Bob Jones University.

He then decided that he wanted to pursue a career in law. He took the Law School Admissions test, the LSAT, and made a perfect score - an almost unheard-of accomplishment that is attained by very few.

Russell was accepted at The Harvard Law School, where again he proceeded to become an accomplished and distinguished student, soon becoming the editor-and-chief of the Harvard Conservative law journal.

After Law School, as Russell's career as a lawyer went on, Russell's health began to decline. Many years went by, Russell getting sick more and more frequently as the years went on, not ever finding the cause of his illnesses. No one knows where it happened or even when it happened, but eventually it was discovered that Russell had contracted a debilitating disease, a disease that had wrecked havoc on his body, often leaving him weak and in pain. Once it was discovered what this disease was, Russell, Beth and his children did what they could to help him, going to profound lengths and back again, venturing forth on their own to find a cure.

And indeed, their prayers and efforts succeeded in helping Russell extend his life for some time, far beyond that which may have been. But the damage the disease had caused over the years was considerable, and it came time for Russell to shed this mortal coil, to move forth into the light of a new body, his Heavenly body with Christ.

Russell Reach has left us in body, and his soul is now with Our Father in Heaven. But his amazing Spirit lives before our very eyes today in six remarkable children that have grown into six incredible bright young adults, each having outstanding character in their own right, each possessing unique personal traits that stand as testament to the service and character of their father.

First of all there's Emily, the oldest, who like Russell is filled with knowledge and a desire to share and instruct; a Bob Jones graduate, who has become a popular and well-liked high school teacher at a local school here in Greenville.

There's Phillip, who, like his dad, is a mechanical genius, a future inventor; a strong man, hard working, filled with a wonderful sence of humor and tenacity.

Next, Daniel, also a Bob Jones graduate, a prodigious mathematician, and also a master of dry wit.

There's Rebecca, who is at a University in Cincinnati, Ohio, majoring in International Business and Foreign language.

Next, Sara, an aspiring writer, and singer, soon to be enrolled as a student at the University of Georgia.

Abigail, or Abby as she's known, who like her father, is an amazing and talented actress, winning a spot last summer with the South Carolina Governor's honors program for Dramatic Arts.

Incidentally, each of these six young people has inherited a talent for music; every one of them sings and each one plays a musical instrument. Today we pay homage to Russell Reach, but also to his legacy, these six wonderful people, each of whom I love dearly, and each of whom, are individuals that we can admire and be proud of. Thank you, Russell, for your service and devotion to them.

Lastly, I would like take this opportunity to mention a speech Russell made, this month back in 1993. Dr. Bob Jones III asked Russell to address the Student and Faculty body at Bob Jones University in Rodehaver Auditorium, to give his testimony about his personal salvation. If you have not heard this testimony, I would strongly encourage you to do so; the recording is available online at reachlaw.com (edit - now available at russellreach.com). Also, I understand the recording will be played at the reception following this service, but I would encourage you, if you want to really get a sense of who Russell was, go home and listen to the testimony in its entirety.

As a side note, I'd like to add that I am most likely, correct in saying that Russell Reach is distinguished as the ONLY person in history to stand before the Bob Jones University student body and faculty, and do an impression of Darth Vader.

However, I have no intention of re-creating that impression, but I DO have my own Darth Vader impression, and it's not half-bad.

Russell, we will miss you. We will miss your laughter, your warmth, your generosity, your kindness. But missing you will be a small price to pay for the joys we are left with, the many things you have taught us, the inspirations you have caused in our hearts, and the legacy of wonderful memories that you leave us. And forever, for the rest of our lives, whenever we hear a certain song or see a picture of a certain place, we shall think of you, and smile.

One of Russell's favorite songs he heard as a child, a song he sang his whole life through, concludes:

"Time it was, and what a time it was;

A time of innocence, a time of confidences.

Long ago, it must be; I have a photograph;

Preserve your memories - they're all that's left you."**

**Simon & Garfunkel, "Old Friends"

-

Eulogy by daughter Emily Reach

When I first started trying to write this eulogy, my Uncle David told me that I would have to follow my dad's signature formula. That I would have to boil everything about my dad down to one word or phrase and work out all the applications of that word or phrase in his life.

So, I started looking for a good word . . . a eu logos . . . for my dad. Many of you have sent me words about my dad in the past week and, since I know that great writing is always some combination of effective recycling and creative plagiarism, I started there. You told me that my dad is creative, kind, inspiring, smart, compassionate, cool, empathetic, energetic, funny, loving, generous, talented . . . and all of these words seem perfect and not good enough at the same time. Not big enough.

But many of you also told me that you're going to miss talking to my dad. So many of you said this exact phrase. I'm going to miss talking to your dad . . . that it became a theme in my mind. In fact, when I think about my dad, the only word that comes close to fully encapsulating his personality is . . . words.

We have many sayings about "talk" that make us start to doubt its value. Talk is cheap, all talk, no action, better to keep your mouth shut and be thought a fool than to open it and remove all doubt, close your mouth and open your mind.

People speak of rather scary and off-putting men in low tones of respect, saying: "He's a man of few words."

And while that man might be more stoic, more dignified, more successful, more revered . . . he is a lot less like my dad. You see, my dad was a man of many words. And most of them were good.

I think of all the times Mrs. Day has sat at our table, playing word games with my dad. Of how he could make her laugh . . . hard but almost silently . . . at his word tricks. He really loved to make her laugh, because her laugh made him laugh.

My dad did not think talk was cheap. He labored at his writing. He would want to be remembered as a writer, and he believed in the power of words. Any time any of us kids got short-changed or ripped off . . . or got our feelings hurt, he immediately started working on a "strongly-worded letter.” That was the greatest threat he could think of. It was his ultimate protection. And, if it was really important, he pulled out the letterhead.

My friends all loved talking to my parents. All of our friends did. Teenagers. While most parents I knew were trying to figure out how to talk to their teens, my parents always had a houseful of them, sitting around the fire, the island in the kitchen, doing chores and talking. I remember one time, in high school, I was at the beach. I called home and one of my friends answered the phone. It was a little disconcerting but, during the course of our conversation, I found out that five of my friends were at my house, in my kitchen, and that they'd known I was gone. They came by to talk to my parents.

It was my dad's love of words, and good conversation, that led him to my mom in the first place. They often told me that, after their first date, they stayed up all night talking. My parents never got over their love of talking to each other . . . I think half of the reason that they liked to take long car trips was the opportunity they got to talk to each other without interruption.

My parents loved to create new words together, and to think of new definitions for old ones. I was in 7th grade, on a youth group ski trip, when I learned that shouting "Let's vandalize!" doesn't mean "everyone hurry up and get in the van, we're about to be late" in the real world.

And I shared this love of words with my dad. This was our main point of connection. I have spent a third of my life officially learning or teaching about words. Learning how to put words together. How to pull words apart. But my unofficial writing teacher, my first teacher, my best teacher, was my dad. He was my writing coach in college and in grad. school. So many nights he noticed the vague look of panic in my eyes, took pity on me, put on a pot of coffee and stayed up with me, listening to my writing, saying: "That's not exactly the word you want there."

When I moved away to grad school, most of my papers began as emails to him. I would write: Hey Dad, I'm thinking about writing about _____________ and then launch in to my paper. I'm not sure if he read the stuff, but I always found it easier to write imagining him as my audience.

And now, here I am. Last night, I faced the toughest writing assignment of my life, without my writing partner. But I do know what he would say. So, in a way, I wrote this with my dad:

I was sitting at his desk at midnight, head in my hands, with all of my ideas, and outlines and research stretched in front of me . . . written on 3 x 5 cards and napkins and on the backs of receipts . . . when my dad shuffled into the kitchen to reload the dishwasher to his liking. He glanced over at me and I looked up:

“Oh. Dad? I thought you’d gone already.”

“No, I have a few things to straighten up here.”

I thought he was talking about me, but he pointed to the dishes. He arranged the coffee cups so that all the handles faced the same direction, at the exact same angle. Then he moved to the bowls. He glanced over again.

“When’s it due?”

"Tomorrow morning."

"Can you get some grace? Ask for an extension?"

"No. Not . . . not for this. It has to be tomorrow morning. Everyone's going to be there. I’ve used up all my grace. We’re out of time."

He sighed, finished with the dishes, put on the coffee, walked over, and told me the elephant statue analogy:

"Em, there was this reporter who became fascinated by the creative process. So, he asked a sculptor: ‘How do you take an unformed block of marble and turn it into a statue of an elephant? Where do you even begin?’ The sculptor replied: ‘I just start cutting away everything that doesn't look like an elephant.’"

I’d heard this story before, and I knew where it was going.

"The first thing you have to do is make your task manageable. Em, there's some good stuff . . . some great stuff in your research and brainstorming that isn't going to work. It doesn't look like your paper, and you're going to have to make your cuts."

My dad has always been really, really good at making cuts. To him, the process and the product are essentially intertwined. He’s good at seeing the finished product from the start – whether it’s a perfectly trimmed plant, a perfectly organized house, or a perfectly executed trip to Disney World – and cutting out what’s unnecessary.

I remember, watching him build things, I'd marvel at how quickly he could make his cuts. I'd usually ask: "Dad? Are you sure you got that measurement . . . "

"Yep." Zip. Zip. Perfect every time.

But I’ve never been quite as good at making cuts. My hands aren’t as sure. And I'm having a harder time than usual today, because everything looks like my dad right now.

Apparently, I'm not the only person having this problem. Of all the lovely emails and cards I've gotten, telling me things I knew and didn't know about my dad, this explanation of his personality resonated most deeply. I really couldn't say it any better:

One thing that came to me thinking about what I know of your dad, considering the vast sweep of his life the thing that most intrigued me or most compelled me to want to know him and be his friend is the way he made contradictory goals compatible. The way he consistently integrated things that seemed to be in opposition to each other. I might be willing to argue that the essence of America’s genius, America at its smartest is America figuring out how to do both: Wage war and eliminate casualties, grow the private sector and make the government work better, help the poor and teach them to work. In that sense I see your dad as a uniquely American genius, a man made for America, a man built to thrive in a country and at a time when genius was the “And.”

He was a man of startling achievement and genuine humility. He was a man of reason, law, logic and imagination. He was a man of dependability and trust and spontaneity and surprise. He was a man of BJU convictions and New Testament agape. He was a man of his sons and a man of his daughters. A man of the South and the North. A man of Yes and No. A man of the mind and a man of the heart.

Insomuch as I know your father, I know him in this way: Both. The genius of the “And.”

Although I couldn't say it better, I could say more.

He was a man of the morning and the evening. Always the last to go to bed and the first to wake up. He was a man who had really strong opinions about the smallest possible things. My siblings and I all got how-to lessons: how to correctly tear a sheet of paper from a legal pad, how to eat our cereal in order to get the correct ratio of cereal to milk, how to organize our closets so that we could get dressed in five minutes. He was a man of these strong opinions and a man of broad perspective and incredible balance.

He was a man who loved to save money, but he also loved salesmen. Not quite as much as they loved him. My dad was a man of breathtaking generosity and ridiculous frugality. He gave of himself ungrudgingly, freely and fully. But I know all of my siblings have experienced the mortification of going to a fast food restaurant with my dad. He always shook the fry container to settle the contents and then marched back up to the counter to ask the poor cashier: "You call this a large fry?"

He was a man of frustrating obliviousness and startling insight. A man of thought and action, an introvert and an extrovert.

It’s true. He did resolve, blend together, a lot of contradictory things in life. But there were things he never fully resolved. One thing stands out particularly in my mind – he never liked being a lawyer. Not on a consistent basis. He didn’t feel that it was his highest calling. But he loved being everybody’s advocate. He loved to take something or someone and make it better, to amplify it, to make it bigger. And people with big ideas and plans found my dad.

Where do I begin with my dad? What do I focus on? It would be easy to focus on his intelligence. His impressive education, his ability to think. Many of you have mentioned these things in the past week. But that's not why you’re here today. You aren't here because my dad was interesting, but because he was interested. It wasn't that a smart man talked to you, but that a smart man talked to you.

If I have to cut (and I do), I will cut everything about my father that doesn't deal with his relationships with other people. He didn't just know and love words – he knew and loved conversation. The human connections, the human possibilities, he created with his words.

While I grudgingly made my cuts, my dad went to get another cup of coffee. When he got back, he looked approvingly at my shrinking pile.

He sat down, took a sip, and said:

“Looks like you’re ready to start writing. Just remember to start with the 500-pound gorilla in the room.”

My dad said this to me a lot. He meant that I have to begin by stating the obvious. I have to take what everyone knows is there but nobody mentions, and I have to look at it, and I have to make peace with it, and then I have to say it.

The difference between good writers and great writers is that the great writers start with the obvious. They start with the 500-pound gorilla.

And the 500-pound gorilla in this room is the Lyme disease. This serious-strange disease that put stress and strain on all my dad’s most cherished relationships, including those in his own family and in his church family. This either-or disease that struck down the Genius of the And.

Already, over the past week, I’ve heard many of you talking all around the Lyme disease. Trying to ignore it. But the 500-pound Gorilla is still here. It’s here now.

In this room, today, there is the grief, yes. The grief and loss I knew would be here. But there is something else, too – an almost palpable feeling of regret. The overwhelming oppression of waste. I think you feel it too, so I have to say something about it – I have to acknowledge it.

We shouldn’t be surprised. Sickness left untreated, or treated improperly, always leads to waste. To wasting away. My dad’s sickness was, too often, misdiagnosed, mistreated, and simply missed. And we all have to do better. As a group, we are too turned off by deformity and decay, too afraid of weakness, too ready to ignore our own and others’ wasting, too reluctant to claim the fellowship we should have in suffering, too quick to find fault, too slow to show pity.

One of the reasons I wrote this eulogy last night is because I procrastinate. But the other reason is that, thinking of who would be here today – thinking about stepping back in this church after my prolonged absence – I was at a loss for what to say. For how to say it. And a part of me, a big part of me, wanted to get up to this podium and scream profanities at the sky and sit back down. I may still do that if I find I can’t get through.

But the other part of me, the better part of me, knows that I’m not here for myself. And I’m not here to make a point. I’m here because I love my dad. I’m here to make sure that the people he loved, the people who love him, understand him – fully, wholly, and generously.

To begin to understand my dad, you’d have to know two things. Two things he taught all his kids early and often.

First, he taught us to beware of false dichotomies. Of treating our problems like either-or scenarios when we don’t have to. Of course, there are some true dichotomies, but not as many as we might think. One true dichotomy is the separation between the living and the not living. That, as I understood perfectly last Sunday night, is a profound and true dichotomy.

There is a tendency, though, when someone dies, to deify that person. To assume he was perfect. Right about everything. That you were wrong. And to let the regret settle in. My dad would be the first to tell you that you’re falling into the false dichotomy trap. In his case, as in most others, there is no either-or. Over the last 10 to 15 years, my dad tried to tell the story of his sickness – but it wasn’t all the sickness. Sometimes he was sick, sometimes he was selfish, sometimes graceful, sometimes sinful, sometimes weak, sometimes strong. But he needed kindness and love at every point, in every state and between states. Because love, also, is never an either-or proposition.

Second, and more importantly, he taught us grace. My dad taught grace differently than I’ve learned it elsewhere. To him, grace was operational and imminent, not transcendent. That is, grace is only grace if you use it, if you give it away, if you keep it current. And the trick of grace is that it doesn’t stay grace forever. Not even God’s grace stays grace forever. At some point, it becomes equality, becomes level. Grace becomes a leveling. The giver stoops. Or the receiver is lifted up. Grace isn’t something you dispense from up high so that you can remain on top. That is power, or guilt, or something else – but not grace. Grace operates from the ground up. Grace operates out of humility. We have to be able, be willing, to give grace even in the midst of failure, sorrow, and pain, or it’s not grace.

In his last act on earth, at his darkest point, Jesus gave grace – and he gave this grace by making himself our equal, by lowering himself. He asked God to forgive us. He told the thief next to him: “You and me. Us. We’ll be together.” And, sometime in the future, he’ll practice grace again by lifting us up. Us. Equal with God.

This is the type of grace my dad taught and practiced. Many, many times when I came home from school or work, I caught my dad taking a quick nap on the couch. He always tried to explain his fatigue away: “Emily…I'm only lying here for a minute...I'm feeling fine, just had an early morning...I’m making progress…This is only a minor setback, a small bump on the road to recovery…The general trend is up."

He was dispensing grace. In the midst of his disease, his greatest concern was how it affected me. How his weakness was affecting other people.

And he would want me to dispense grace now. He would want me to give grace, even (especially) from my lowest place. He would want me to tell you . . . it’s ok that you didn’t always understand him, that you didn’t always understand the illness. He would want me to acknowledge our equality – I lived with it, we lived with it, and we didn’t always understand it. We got it wrong most days. He would want me to tell you that he’s only lying here for a minute, that the general trend is up. He would want me thank you for taking care of us over the past week, to thank you for loving us, and to thank you for loving him every way you knew how.

After I dealt with the obvious, my dad glanced at me over his coffee and reminded me to make it a story.

My dad always told me to use story-telling techniques, even when I was writing the most prosaic research paper, because people want to hear stories, not big ideas. He was obsessed with circles and cycles and titles and relationships. He knew that words and writing are all about relationships.

He loved stories where the stranger in chapter 4 becomes significant in chapter 17. Where ideas and characters come full circle and everything makes sense in the end. Stories where even the names are meaningful, where the heroes have names that sound heroic and the villains have names that sound villainous.

That's why my dad loved the Bible, the greatest story ever told. He loved the circles, the cycles of living and dying, belief and unbelief. The generations. He loved the naming, the un-naming, and the renaming. The visions and revisions. My dad believed that constant revision is the right of every human, and the responsibility of every human who believes. Constant revision, re-circling, recycling. Multiple opportunities to get it right.

And now, I'm trying to come to terms with how short my dad's story was. It was too short. And seemingly incomplete. It doesn't feel like it has come full circle . . . that his experiences are making sense in the end.

It's not the story I would have written for him.

But I have managed to see a few circles in my dad's life during the past week. A few motifs that have cycled through.

He began his life as the leader of our family while traveling with my mom on Doug Henning's World of Magic tour . . . and he ended it with his two youngest daughters at the Magic Kingdom. He would like that irony. He started his family here in Greenville, moved to Boston, to Houston, to Atlanta, and then brought us back here. When he was first here in Greenville, he lived off of Piney Mountain Road, in a white house right behind the cemetery we'll be going to in a few minutes. He used to, on his walk home from Bob Jones, steal flowers from that cemetery and bring them to my mom . . . you know, he wouldn't take them off the graves, but they went through once a week and took all the flowers off and put them in this big trash heap right beside my parent's house. He retrieved the bunches that still looked good, still had some life in them, and gave her those. We're about to bury him within eyesight of that same backyard.

And meaningful names? Well, I can't imagine my dad could have been any more pleased with his own name. It's a great name for a hero . . . and it described him perfectly.

Reach.

Both a noun and a verb. Aspirational, inspirational.

My dad hated it when people took declarative statements in the Bible and made them imperative. For example, something like: "Having therefore fellowship in Christ . . . " becomes "Now guys, we need to have fellowship in Christ." This really irked him. It was a personal pet peeve.

So, it's a little ironic that, read one way, his last name actually is an imperative. A command.

Russell (comma) Reach.

As if God himself had ordained my dad's life to be a struggle, a straining, and a striving. Russell. Reach.

And my dad did reach. He did listen to the imperative of his own name, even when reaching became difficult. He listened too well, according to some of us.

You see, I think we have only two accepted sickness narratives. There’s the plot where the sick person, and those around him, fight valiantly, patiently and calmly. And they overcome. And there’s the plot where the sick person, and those around him, make peace with the disease and each other. And then the sick person dies. Peacefully.

My dad didn’t fit into either of these narratives. His story was much truer and much more complex. It was the story of someone who fought, but fought messily, who kicked against his affliction, who never made peace with it – and then died anyway. That’s a story that makes us uncomfortable.

In church and on the news, in popular culture, I've heard story after story of people who, in tough situations, dealing with family illnesses like we have. Well, they somehow "never made a peep."

And I've thought . . . if only I could have learned to peep a little less. If only my dad had learned to peep a little less.

And I’ve thought. Maybe they were right. Maybe that was the way to go. Maybe we should have learned to "let go and let God."

But . . . then I start to question the modern Christian equation: Compliance + Silence = God. Equals godliness and goodness. Maybe it just equals giving up. Maybe that’s a formula for comfort, not for godliness. Maybe letting go isn't GOD. Maybe God is grabbing on. Tight. Maybe God is refusing to let go, refusing to give in.

And, ultimately, what I see in the Bible is that the kickers (Paul & Peter), the wrestlers (Jacob), and the failers (David) get the biggest blessings and have the most influence.

Every character in the Bible (and, anyone who knows anything about Literature knows that the best authors reveal their themes through the actions of their characters) every character is a fighter. Every character is a failer. A failure. They are not compliant. They are not silent. They are not comfortable . . . in their faith or in the world.

Robert Browning once said: “A man’s reach should exceed his grasp.”

What do we do, then, with a man like my dad? What do we do with someone who grasps ideas so quickly, who cuts to the core of an issue immediately – so that it seems more like intuition than what could rightly be called a thought process – a man who grasps people so profoundly? In other words, what do we do with greatness? How far should a great man reach? How far does he have to reach in order to exceed his grasp?

I mentioned earlier that we don’t tend to do well with sickness, with deformity, with weakness. We’re also not that good with greatness. With exceptionality. Both extremes make us incredibly nervous – incredibly uncomfortable. And my dad was both; he was weak and he was great. Like he was tailor-made to put us all on edge.

We have a tendency to try to harness greatness, to try to bottle it. To tell it to pipe down. To shut up. To peep less. To quit telling its story. We tend to want to put great people in their place.

But maybe my dad was already in his place. Maybe "Reach" was his job, not just his name. Maybe “Reach” was exactly what God wanted my dad to do, who he wanted him to be. Maybe it was my dad’s way of occupying his space in the greatest story ever told. I think that may be true.

So, I am happy to report – even as he lost his grasp on people, places, priorities. Even as he lost his grasp on words, even as his abilities plummeted. Even as the vast sweep of his life spiraled inward, even as his sphere of influence shrunk, even as every aspect of his being became more and more limited. More and more insular. Even as he lost his grasp on his own life – I am happy and I am proud to report: my dad always maintained his Reach.

My dad stood up and stretched and yawned. I looked up from my work:

“Well? Is it OK?”

He arched an eyebrow at me. He nodded.

“It’s more than OK. It’s perfect. Very logical.”

He shook his head.

To my dad, “perfect” and “logical” weren’t necessarily compliments. I sighed, because I knew what he was going to say next.

He had a lot of ways of saying the next step. He would say: “Now you need to peel away one layer of logic. You need to back away a little from your reason. You need to make it more visceral, trust your instincts.”

“You need to mess it up…on purpose. Just a little.”

He always said I was going to be a great writer so he’d say: “You’ve got to give your critics something to argue about. If it’s reasoned and logical all the way through, then you’re never going to be great, because people remember the mistakes. People love the mistakes.”

And what he meant by all this was . . . you’ve got to be a little vulnerable, be a little human.

And that’s really hard. It’s hard for me to be even the smallest bit human. Especially here. Especially in front of all of you.

It’s hard for me to admit that, as a grown woman, I’ve been creating circles for my dad because I knew he liked them. That part of the reason I went to Miami University was because I knew it would make him happy. It would make him feel like our story had structure. That part of the reason I moved up to Boston was to find him. That part of the reason I moved back home was that I realized he wasn’t there.

That’s all very, very hard to admit. It makes me feel foolish. It makes me feel duped and cheated. But it’s also the truth. The truth is I’ve been collecting my dad ever since I discovered he was missing.

The way I feel, when I’m being honest, vulnerable, and human isn’t logical or faithful. Logically, I know that everybody dies and that this day was inevitable. By faith, I believe, I know, that he has victory in death.

But I wanted him to have victory here, in life – really badly. I wanted that victory more than I wanted anything else in my entire life. I wanted the spectacular recovery narrative – and, more than that, I wanted other people to know that my dad had victory. That we had victory. And it didn’t happen.

The only consolation I have – the only thing that makes this conspicuous defeat even slightly bearable – is the knowledge that my mom and my brothers and sisters wanted and worked for the victory, too. And all I can say to all of you is: “I know.”

We never talked about it, but I know that’s why whenever I went home, whenever I was drawn home, chances were that one of you had arrived moments before me, or would be following moments after. I know what it felt like to put your hand on the doorknob and feel the question burn into your palm: Will he be here today? I know what it felt like when we could talk to him, and I know what it felt like when we couldn’t. I know why we jokingly said that each day, sometimes each moment, was a Russell Roulette. I know why that joke was funny, and I know why it wasn’t.

Mom, I know that lots of people said that you should leave, and I know why you didn’t. Phil, I know why you called home to ask dad building and car questions – even when you already knew the answer. Dan, I know why you started going with dad on his business meetings – why you started working for his law firm, even though it wasn’t always easy. Becky, I know why you often came home with “leftovers” of dad’s favorite foods – I know why you ordered too much. Sarah, I know why you got off work to go on this vacation. And I want you to know that he told me at least five times that you’d gotten off work to take a trip with him. I want you to know how much that meant to him. And Abbey, Doodlebug. I know why you wanted this trip in the first place. I know what it was supposed to mean, I understand the symbolism of it, and I’m very, very sorry.

I know. I know all of it. I know what kept us all circling, hovering around our house like anti-vultures, prodding for signs of life, waiting for the good words to come back.

I know what we all wanted, and I know it wasn’t this.

After I messed it up, I was tired – exhausted – and I wanted to stop. But my dad told me to recover and write it all the way to the end.

And then he put his empty coffee cup in the dishwasher, and then he left, and then he was really gone.

He always leaves me to write the end on my own. So that what I write will be my own.

Write it to the end – the one you had in mind from the beginning. I learned this writing technique later in grad school, but my dad taught me first. Start with the end. Write with the end in mind.

This is what God does, in the world and in our lives. He writes ours lives and the history of the world with the end in mind.

And the end brings us back to words.

My dad and I believe that words are the most creative and eternal thing we have on Earth. We believe that words are not only little slips of value like money or little containers for meaning – that words don't merely express truth or carry truth or contain truth – although they do do these things. But that words can also create truth. That you can make something be true by saying it. By declaring it.

The best example is God, who literally created physical things by speaking. But, after him, there have been people (made in his image) who have that same power to a lesser degree. People who can create truth and make things be just by saying that they are. And my dad was one of those people.

I’m sure my dad would not be shocked to learn that, after a certain age, the only way to increase your IQ, to create new connections, new synapses in your brain, is to learn new words. To build your vocabulary.

And, as much as I adore my little brother, and think his obsession with math is cute, I’m not at all surprised that there was never an integer that was made flesh to dwell among us. Because Math describes, categorizes, postulates, orders, delineates . . . but it doesn't create. Not like words do.

And as proud as scientists and mathematicians are of their logic, I can't help noticing that "logic" comes from logos. Which means word. And I think logic and magic are the same thing. That they are intimately related.

I think that all of these things are intimately related, and that words are all about relationships. That’s what we’re here to celebrate today. The new connections and the new relationships that my dad created with his incredible talent for words.

That’s why you’re here today. You’re here because you’re going to miss talking to my dad. You’re here because my dad talked to you – and, as he talked to you, he made you who you are.

To some of you he said: “You have an entrepreneurial spirit, but you’re living a life of no risk.” And you started taking risks. To some of you he said: “You have a passion for children, but you’re putting off having any.” And you started a family. To some of you he said: “Your heart is overseas, but you’re here.” And you moved.

To me he said: “You’re a writer.” And I didn’t go to Med School.

The thing that bothered me the most when I heard about my dad’s death is that all of those connections that he built so carefully, all of his life’s vocabulary, went with him – that he got to take it with him. I wanted him to leave it here. I wanted him to keep the conversation going. I wanted to talk to my dad for the rest of my life. I will talk to him for the rest of my life – even if it’s only in my own head.

But my dad has been translated. He has been given a new vocabulary, and it's one I don’t understand. He has new words, and, I think, a new name. His reaching is over. Maybe God will let him rest, change his name from an imperative to a declarative. Maybe now he's “Russell Builds” or “Russell Sings.” Or, maybe (and this is my vote) maybe simply “Russell Is.”

The end brings us back to words. And in the end, I’m happy for my dad’s values, his priorities, and his vocabulary. Because people who delight in words, and in the Word, get to enjoy them forever.

<

>

The purpose of russellreach.com is simple - we hope to spark some fair memories of Russell that will bring a fresh wave of joy and inspiration to you.

It seems so obvious that this was one of Russell's goals and talents in life - to bring passion, inspiration, and joyful memories into the lives he touched.

%20copy.jpg)

%20copy371x286.jpg)